…but that doesn’t mean we’re not right.

Just some stuff I saw on TV this week… or was it in a few years’ time?

|

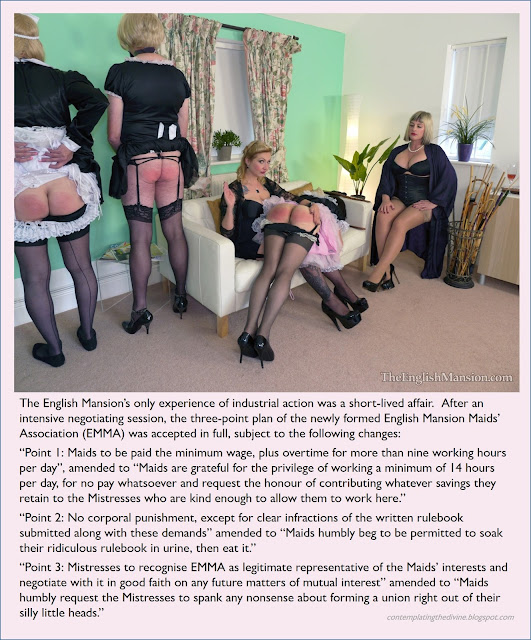

| She’s an expert negotiator. |

|

| Warning: the value of investment bankers can go down as well as up. |

|

| There’s also ‘maidspreading’. That’s when you stand with your legs held firmly apart with a spreader bar. It’s usually a precursor to something rather painful. |

|

| You’d think they’d have guessed from the spreader gag. |

I know you all prefer the visions of a matriarchal future under the loving but firm hand of the divine Anne, but this blog is merely a place to record the facts and my time viewing device thingy does seem more and more often to indicate the coming of an altogther darker time.

That said, this future is only dark, bleak and brutal for males. So as far as human rights for actual humans are concerned, things are looking pretty good!

… or should that be the other way around? More visions of a possible future, anyway, lots more here.

On the way to a better tomorrow.

Just been sent some campaign material by a certain political party. Probbaly going to be seeing these on billboards all across the country in the run-up to 2020.

That’s all the campaign material I have for now. Well, there was one more thing in the box. But I don’t think this was intended for publication – looks like their agency’s briefing on a TV spot they’re planning. Can someone let me know if they ever see the finished ad?

A bleak, totalitarian vision… just for a bit of sexy fun, obviously.

I know this isn’t everyone’s cup of tea. There’ll be more tender, loving maternal discipline posts just as soon as I’ve completed my stint in the re-education camp, OK? Shouldn’t be more than twenty years, twenty-five tops.

I know you all yearn for a Goverment committeed to the smack of firm but loving matriarchal discipline but if we’ve learnt anything over the last year or two, it’s that in politics anything can happen and it doesn’t always turn out the way we might like.

As for those males commited to absurd old-fashioned notions like sexual equality and who might think that the future envisaged under President Hathaway is oppressive (to be honest, not many such males read this blog), they need to be aware that another world is certainly possible.

I was going to say “your choice, guys”. But of course, it won’t be.

By popular demand*, more scenes from the 2020 election campaign and the Hathaway administration’s first term.**

These ones seem quite heavily to feature Megyn Kelly***. If you object to that****, perhaps you could direct me to other ladies whose image on TV has been captured in quite so many high quality screenshots.

* No, really, just for once. Honestly, I write a blog full of pictures of sexy young women wearing not much, or kinky leather-clad vixens and what do you all clamour for? More posts about politics! You’re a bunch of very weird people, you know that, right? But then, so am I.

** See those little underliney things? Those show the words are actually links: to earlier posts in this series. Apologies to female readers of this blog, who are obviously able to work that out for themselves.

*** Who appears to have taken on a role as spokeswoman for the campaign while retaining her anchorwoman job. If you think that’s a conflict of interest then take it up with her, not me, OK? But be polite. Very polite.

**** No, I’m not expecting a great many objections either. But you never know.