So… a few years back I wrote two parts of a Serena and Alice story based on Portal, the truly wonderful game about jumping through transdimensional hoopy things. And always intended to write a third part, maybe about using portals inside slaves’ bodies to make them into more effective human furniture, or something, I dunno. But it never quite happened and so the story was left hanging, in a frustrating manner (and not ‘frustrating’ in a good way).

And last week someone left a comment on the second part, all the way back in 2018, asking where the third part is. And that kind of shamed me (also not in a good way, although I do very much enjoy being shamed, in certain contexts) and inspired me finally to write Part 3. So here we are, Serena and Alice, Thinking with Portals Part 3.

Anyone not familiar with Serena and Alice might want to go and check out some of the previous ones. Or just run away. What follows contains scenes of extreme violence, non-consensual torture and murder, along with a lot of lesbian innuendo. It’s a Serena and Alice story for goddess’ sake! That’s what they do and they’re very good at it. If you don’t like that sort of thing, don’t read it. And if you do like that sort of thing, you’re a despicable human being and probably a danger to society, just like me.

Here we go.

It’s hard to overstate my satisfaction

her. “What are you doing?”

A tall, dark-haired girl looked back up at her. She was notionally dressed in the same school

uniform, but where the blonde somehow managed to fill out the costume in a traditional

– if cutely sexy – manner, she instead seemed to take an alternative slant on

every item, from the skirt slashed diagonally, via the tie being used as a

belt, to the asymmetrically-buttoned blouse.

And where the blonde’s hair cascaded into golden curls, the dark hair

before her was slashed in random places – as if by a razor, which indeed it had

been. She said nothing.

“You’re that weird goth-girl aren’t you?” the blonde

added. “Why are you sitting on that

boy?”

The other girl’s purple-highlighted eyes narrowed slightly.

“And you’re that blonde airhead. One of

the ‘popular’ girls.”

She glanced down.

Below her, occasionally wriggling slightly, was a figure in the male

version of that same uniform. He was lying flat on his front, the girl’s weight

pressing into the small of his back, his face smooshed onto the muddy gravel by the

ankle of one of her heavily booted feet resting on the back of his head.

“I’m sitting on him because it’s more comfortable than

sitting on the ground.”

“Does he like it?”

The other one shrugged, causing the boy to yelp as her

weight must have pressed some bony part of his anatomy to the ground.

“Don’t think so. A

few do – or they think they do until it gets serious. But this one’s just scared of me. Aren’t you, maggot!”

The ‘maggot’ sobbed a few indistinct words of

acknowledgement.

“I can make him do anything” she added, “Anything at all. Look.”

And she lifted her boot, extended her leg out, then scraped the heel back along the ground, building up a mass of mud and gravel pieces, and continued scraping until the filthy mess was in contact with the boy’s lips.

“Eat!”

Trembling lips closed around the slick, muddy mess and a

mouth frantically worked to remove it from the leather.

“That’s bullying!” the blonde declared firmly. “The school has a policy on bullying, you

know.”

“So do I” smiled the other.

“This is it.”

The blonde smiled back uncertainly, not used to seeing a

happy expression on the face of the weird goth-girl that she and all her

‘popular’ friends had always avoided.

“Oh come on” the goth-girl said. “Haven’t you ever thought about what you

would do if you had someone helpless – completely helpless? And you could do anything you want to them?

Anything at all…?”

The blonde tossed her head proudly. “I can get boys to do just about anything I

want anyway.” She said. “Waiting for me,

falling in love… presents.”

“I really like presents”, she continued, thoughtfully.

“This one never buys me presents” the seated girl

remarked. “Because he never has any

money, because he gives his pocket money to me on the day he gets it. Don’t you, maggot?”

Her seat gurgled his assent, apparently trying to swallow a

particularly troublesome lump of gravel.

“So… so, OK.” the blonde nodded. She could see the point of that. “And you

don’t even have to have sex with them?”

“I don’t really like sex with boys” the other replied. She looked up, again.

“Not with boys” she repeated.

The blonde wasn’t paying much attention, her gaze fixed on

the brutalised boy, who was now frantically licking the seam of the boot before

him, trying to restore it to the pristine condition it had been in before it

had been used to scrape up his indigestible meal.

“I suppose you could… could make them do sex the way you

wanted it, instead of the way they like it” she murmured thoughtfully. “Using their tongues more, for instance. For longer.”

“I mean, not this one obviously” she added, wrinkling her

shapely nose in disgust at the blackened tongue. “Not after where that’s been.”

“Plenty more of them.” the other replied disdainfully. “Honestly, there’s no shortage of males in

this world – nasty brutish things. But

you know, girls have tongues too. And

they taste nicer. How about letting me

show you?”

She shuffled back slightly on the boy’s back, to make enough

space for a second person. They boy,

realising what was about to happen, started taking deep breaths as if

oxygenating his bloodstream for a deep dive under the ocean.

“Well, I’m not sure” the blonde replied, but, rather

uncertainly, she stepped over the prostrate form, took the other girl’s

proffered hand and lowered herself onto the waiting back.

“Whoops” she cried out, toppling sideways, but an arm reached

out quickly to grab her waist, steadying her and bringing her back

upright. And then remained around her

waist.

“I’m not a lesbian, you know” she remarked, primly.

“How do you know?

Have you ever had sex with a girl?”

“Well… no.”

“That’s probably why, then.

I wasn’t a lesbian either, before I had a sex with a girl. That’s how you become one – let me show you.”

“Well… maybe just a kiss.

Erm…. Look, sorry but I don’t actually know your real name. I just think of you as ‘weird goth girl’.”

“Serena.” smiled the other, pulling her closer. “And I think I know your name, little blonde

airhead, but I’d love to hear you say it as I kiss those lips.”

“Alice. I’m – oh! –

I’m Alice.”

…

As they leaned into their embrace, and the male below

struggled helplessly to breathe, two shadowy figures vanished in an orange flash behind the nearest bike stand, with an eerie whooshing noise, leaving behind a sharp smell of ozone.

But, engrossed in one another, neither girl noticed any of these things.

…

“That was amazing!” shrieked Alice happily, tumbling

out of the blue-edged time portal in Serena’s laboratory. “How do you turn portals into a time

machine?”

Serena smiled indulgently.

She thought about quantum entanglement, about paired sets of particles

separated through proximity to the event horizon of a minuscule artificial

black hole she had held stable, for the microseconds before it dwindled to nothing from the Hawking

radiation into which its mass had to turn; she thought about the particle accelerator extending out

for miles around the underground facility, in which one of each pair of

particles, accelerated to near the speed of light, found itself separated in

time and space from its stationary counterpart, while still in a deeper sense

remaining adjacent to it in all these dimensions. About manipulation of matter

at the subatomic level, using techniques far in advance of any other

nanotechnology, to seed the paired particles into the matter of a pair of

transdimensional portals…

She thought about these things and also thought about Alice,

about her sparkling blue eyes and her cascading blonde curls.

“Science” she replied.

“And you really were such a goth girl!” Alice

giggled. “I’d forgotten. Purple eye-shadow, Doc Marten

boots… the works.”

“Just a phase” Serena replied, slightly put out. “Anyway, I met a little blonde airhead who

made me happy. And you can’t really keep

doing the goth thing if you’re happy – doesn’t work. I still like The Cure, though.”

“And wasn’t I cute!” Alice gasped. “Oh my god… I could so have fucked

myself.”

“So could I – and I did, just two days later, remember? –

but, you know, I actually prefer the slightly curvier look of you now…” began

Serena, but Alice wasn’t listening.

Instead, she seemed to be thinking hard, her pretty brow

furrowed as it always did when she carried out this out-of-character task.

“Hey” she said slowly.

“We could go and visit me. Or

you! I could fuck two of you at the same

time. I’d like that!”

“But I’d really, really like to fuck myself.” she added,

wistfully. “Can we? Please?”

Serena had been thinking too, as soon as she saw where her

friend’s mind was going. Serena could

think a lot faster than Alice and in any event, had thought of all of this long

before and had even tried it out. So she had

thought a lot more things in the same time, before Alice had formulated her question. Disturbing

things*.

“Multiple us-es” she smiled.

“Maybe not quite such a good idea. Imagine if there were two Serenas and

one had to watch the other kissing you.

You know how jealous I get and when I get jealous I become. – “

“Homicidally violent” Alice nodded. She didn’t know much about science but she

understood Serena and although she loved

her more than anyone or anything in the world, she felt certain that one Serena

was quite dangerous enough, for the world and everyone in it except Alice

herself. Two or even more was a

terrifying prospect.

“But multiple Alices would be OK, though” she pleaded. “We’d just have sex, Lots and lots and lots of sex. Come on – wouldn’t you like to watch me

kissing myself? Wouldn’t you like to be

kissed by two of me – we could kiss you in different places at the same time.”

Serena tried to suppress thoughts of how much she would like

that. She remembered a bedroom, the

flash of orange light as a portal appeared, a delighted cry as one Alice

recognised herself in the other. The

wild, passionate sex, the extraordinary things that Alice could do to her being

done to her twice, multiple times… she remembered all of that and found herself

breathing heavily.

But she also remembered the demands for more Alices. That if sex with two Alices was amazing,

imagine how sex with four would be. Or

more… please? Pleeease?

And she remembered two pairs of blue eyes gazing pleadingly

at her, and how much harder it was to resist than when only one pair did that. And realised – just before pressing the

button to bring another pair of Alices into this universe – how much harder still

it would be to resist four pairs of pleading eyes.

And she remembered envisaging the exponential curves, as

four delighted, squealing orgasming Alices became eight, then sixteen, then

thirty-two and how Serena’s capacity for rational thought – normally superlative but liable to turn to goo when confronted with those dancing

blonde curls – would collapse and the button would be pressed and pressed

again, and the pile of writhing, gasping Alices would grow and grow until the

mass of sexually insatiable Alices began to generate its own gravity field and

the Earth itself crumbled into the event horizon created by a near-infinite replication

of her pretty girlfriend – and she remembered staying her hand and not pressing

the button.

Because, vicious, vindictive and mass-murdering though she

was, Serena did not actually want the world to end. As long as it still had

males in it to torture to death – and as long as it still had Alice, of course

– she rather liked the world. So with a

supreme effort, she had said no, even when both golden-curled heads tossed so

very fetchingly in annoyance and disappointment. Serena, she who could watch acid burning off

the entirety of a man’s flesh, layer by layer, while sipping tea and taking

notes, had to suppress that memory rapidly, with a shudder. Strong as she was, there were things even she

could not bear.

“Not possible” I’m afraid., she replied brightly. “It would create a paradox. Two Alices, occupying the same position, in

time and space…”

“Well, not exactly the same position” Alice said, coyly. “See, I was thinking that I could

go between your legs, while the other Alice…”

“…in time and space”

continued Serena, loudly, “that would break the laws of causality. What you do to the other Alice would be done

to you – in a sense – and –“

“I know: that’s the point.”

“…and if you’ve done something to yourself before the other

one remembers doing it to you, then how can your other self not remember doing

it, when she comes to do it? When she’s

you? A paradox, you see?”

Alice was staring at her blankly.

“Paradox” said Serena, again. She briefly wondered whether Alice knew what

a paradox was.

“I mean it’s against the laws of physics.” she added.

“But I don’t care about the laws of physics!”

retorted Alice, near tears. “I just want

to fuck myself. It’s not as if we care

about other laws, is it? I mean,

kidnapping and torturing and murdering men must be against a whole bunch of

laws, too, right? I mean, I haven’t checked

but it must be. And that’s never stopped

us. Please?”

“The laws of physics are different” began Serena,

weakly. And then she had a brainwave.

“Plus, obviously, if there were two Alices each would

only get half the number of presents” she added, casually. “I mean, that’s just arithmetic: more Alices, fewer presents per Alice. If two Alices were given a pair

of gold ear-rings, for example, oh… say with inlaid rubies, they could each only have one.

Although, I suppose

they could share them… take turns…”

“No, no you’re right.” Alice said, quickly. “Quite right.

That would be awful… imagine having to share presents. I mean, even with myself.” She shuddered.

“And there’s those laws of physics to consider.” she

added. “Mustn’t break those. And all

the paradoxes, the nasty things.”

“Exactly” sighed Serena, making a mental note to compel

someone to buy a very expensive pair of ear-rings. Gold, with rubies. “And you know… I’m very happy with just the

Alice I’ve got. She’s perfect. Now – how about I show you a few tricks with

time-portals?”

And the two friends spent a happy afternoon discovering

ever-new ways of using time travel to inflict pain and suffering on males,

perhaps because the author realised that readers of Contemplating the Divine

might actually want a bit of femdom content, for goddess’ sake, in what has otherwise been

essentially a lesbian love story,* with some slightly ropey science attached.

|

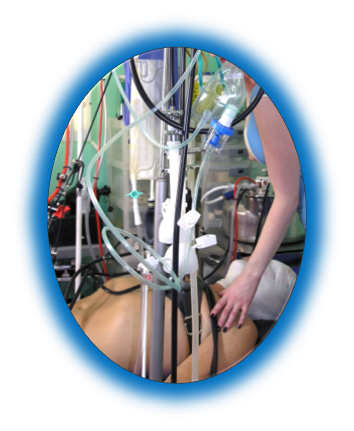

| Aliceworld (in this image Alice is played by an actress who looks a bit like her). OK, I’ll admit there are worse possible fates for the planet but it’s probably still better not to risk it. |

…

Alice giggled as her friend turned a dial and the genitals

of the restrained male before them turned old and wizened, trapped as they were

by a thin band of time portal in an era when this body had become 90 years old**. Then she turned the dial the other way and

after a brief spell as a healthy adult male organ, the penis shrank back into a

twig-like state and the balls lifted up into the helpless male’s crotch.”

“Aww… like a liddle boy” mocked Alice and blew the man the

sort of kiss that could usually raise at least a twitch in the adult male organ

– but of course could do nothing for the pee-pee of a six year-old.

…

They spent a few hours watching the Spanish Inquisition at

work, Serena taking careful notes about the operation of the rack, before

returning to their present with the inquisitors themselves.

“I suppose they’d be interested to see how torture

technology has progressed in the last few centuries” Alice remarked, as she

watched the last of them being lowered automatically into his holding cell,

shrieking in terror and fury in a mixture of Spanish and Latin, about devils,

witches and (she-) demons.

“We could give them a thorough demonstration this Saturday.”

nodded Serena. “I expect they’ll be

quite impressed. Still… they knew how to

make a rack back then. Did you hear when

the tendons around his knee snapped?”

“Pop!” shouted Alice, delightedly. “I love it when that happens. And the

screaming of course. What’s next?”

…

What was next turned out to be two naked males, in a largely

bare room. One was strapped to a table

and had obviously been the recipient of Serena’s attention for some

time already. What remained of his body was

covered in small bloodied cuts and, more importantly, what remained of his body

was not that much. Many of his extremities were missing or had large chunks chopped

out of them. The other male appeared to

be unharmed, seated in a high chair affording him an excellent view of the

torture victim, a view that he could not avoid because his neck and head were

strapped into a steel contraption that forced him to gaze in a prescribed

direction and his eyes, behind transparent plastic lenses of saline solution,

were clipped open. Alice had seen this

before: it was the set-up Serena used when she thought it was important that a

boy should see something that he might otherwise be too terrified to look at.

Serena went over to the quivering bloodied torso and held up

a small steel object with pride.

“All done with just one pair of pliers!” she declared,

flexing her palm to show the blades – which cannot have been longer than one

and half centimetres – opening and closing.

“I thought it would be fun to limit myself just to these,

you see. Like an artist – another

artist, I mean, a different kind of artist from me – limiting herself to

just one brush or some such. And it was

really interesting. Obviously, working

steadily up the joints of each finger was straightforward – that’s what these are really for, after all

– but then for example the larger limb parts presented quite a challenge. It took ages to do this knee for instance”

she said, gesturing casually to the bloodied stump of one leg, where splinters

of twisted and crudely cut bone stuck out of raggedly-abused flesh in which, indeed, each

zig and each zag was no longer than the blades of the pair of pliers.

Alive clapped politely.

“And what about him, then?” she asked, gesturing to the

uninjured male in the chair.

“Is he next?”

Serena chuckled.

“In a way, yes. Look

closely at this one’s face.”

Alice leaned over the savaged bloody mess that had once been

a face, and looked with interest, then glanced back at the figure in the chair.

Reader, if at this point you expect Alice to say something

like “Oh, they’re very similar, are they brothers?” then I must disappoint you. Alice is a little ignorant of certain

scientific, historical, geographical, astronomical, literary and other matters (although she

has unparalleled expertise in certain specific aspects of biology) but she is

not stupid. She got it immediately.

“Ooh! This – “ and she indicated the bloodied mess – “ is

the future him.” and pointed to the immobile figure high in his

chair.

Serena smiled. “That’s right. He’s seeing his future. I’ve been working on him on and off for a few

weeks now; there’s probably a few weeks to go.

He gets videos to review on days when his future self isn’t being

tortured too, so when I send him back to his own time he’ll have a really

excellent knowledge of exactly what will happen. Then from time to time I visit his cell and

bring him here and strap him down. And

on one of those times – it might be the first, it might be the hundredth –

it’ll start.”

“So he’ll see his own death?” Alice asked. “That would be spooky, wouldn’t it? I don’t think I’d like that.”

To her surprise her friend shook her head. “I don’t want to give him the comfort of

knowing when he’ll die. You might

not want to know when you’ll die, but it’s different for them, on the torture

bench, because it’s the one thing they have to look forward to; the thing they

long for more than anything else in the world.”

“No. When he’s not

much more than a cube of living, hurting flesh, I’ll stop and it’ll be for his

former self to imagine how long he has to endure in that state until his body

grants him the privilege of non-existence.”

This was all a bit philosophical for Alice, who was looking

again at the face of the moaning torture victim.

“You haven’t done the eyes yet. Can we do an eye? It must be tricky with the pliers… they’re so

small. I mean, I suppose we could just stab and gouge it out with the blades

together, but it seems a bit too easy for him.”

She paused.

“Hey! How about if we

snipped around his eyeball? Instead of

gouging the eyeball out, we could snip away all the bony bits holding it in,

one at a time. Would that work?”

“Clever you!” Serena said. “I’d been wondering how to do the

eyes. How about you do the cutting too –

I’ll hold his eyelids out to start with, while you snip them off.”

And she handed her friend the pliers and the two happily

went to work, accompanied by the screams of the victim, whose tongue had long

since been too lacerated to allow human speech but whose vocal chords were in

perfect condition for the screaming they so often had to do. Perhaps through the agony he dimly

remembered, too, seeing the same scene from outside, from high up in the chair

where his former self watched, every snip, every twisted off bone, every gouge

cut in quivering flesh adding to his stock of dread for his inevitable fate.

…

“You’d think someone who gave his name to the practice of ‘masochism’ would be better at it.” complained Alice, as they entered the orange portal to return to the 21st century. “And a bit more grateful when someone takes the trouble to show him how femdom techniques developed after his time.”

“Those who can, do, those who can’t, tech” shrugged Serena. “Have you tried this Sachertorte?”

…

Later, in bed, the two reflected on their day.

“You know”, Alice said, “I don’t really see the point in

time travel. I mean, it was fun but

there are lots of other ways to torture boys.

And those history trips were OK, but you can watch a movie instead, and that’s

often … I dunno… more exciting. Except

maybe when we went to that sunny country, where they were nailing guys to those

wooden things… that was nice, and they don’t show those bits in movies, not

properly.”

“You mean, when we witnessed the crucifixion of Christ?”

Serena replied, quietly.

“Yeah, that.” Alice replied.

“Like that Mel Gibson thing. That

was all right, I suppose. But what I

mean, is that I don’t see the point of trying to change the past. Why would we want to do that, when it’s all

been so good?”

“I suppose some people might have regrets… might want to go

back and change things so their lives worked out better.” Serena replied. “Try to warn their former selves about

mistakes they will make.”

“I expect most of the males who’ve ever met me would very

much like to do that, actually.” she reflected.

“Yes, but that’s not us, is it? That’s them, and they don’t matter. Except as slaves and pain-toys. But I mean,

even people who don’t end up being enslaved and tortured might want to

go back and change things… give them some information that might make their

former selves money, for instance, which – “

“Which would reverse the principle of causation and thus

endanger the integrity of the universe.” Serena reminded her.

“Yeah, right. But

even if we could, we wouldn’t want to, would we? I mean, you don’t need any money; you haven’t

since the day that mysterious woman appeared and gave you those winning lottery

numbers, and you used the jackpot to buy your first lab and invent stuff and become

a billionaire, right? So why would we go

back? Life’s perfect and it has been ever since we met.”

“That’s right” Serena replied, thinking it might be best not

to dwell too long on the mysterious stranger she had met soon after leaving

school. “Best not to mess with causative

reality, anyway.”

“Cos of the platypuses” Alice murmured, resting her head

against Serena’s chest and closing her eyes.

“Paradoxes” smiled Serena, kissing her friend’s golden locks and wondering whether her girlfriend had been imagining the world being over-run by scurrying Australian beaver-like animals throughout the earlier discussion of temporal causal loops.

She gazed down at her fondly. Alice was no intellectual, but she had a deep

reserve of common sense that Serena knew she could rely on. Her friend was right, of course. She, Serena, was wealthier than any human in

history, had hundreds of men locked away trembling in terror at the very

thought of her and she could do anything she wanted – anything at all, just as

she had dreamed of, when bullying boys at school. Few people in history had ever

experienced sadistic desires to match hers, but surely none even of those had

ever had the opportunity to put their every vicious desire into practice on such an

endless number and variety of unwilling victims.

Truly, she was blessed, And above

all, she had Alice: beautiful, wise and sexually insatiable.

Why travel into the past, when your life today is perfect?

“Light off” she commanded quietly, and in a neighbouring

room two sweating slaves on stationary bicycles came to an exhausted halt and

the lights in the bedroom dimmed to darkness.

And Serena settled back, her lover’s head heavy on her chest, and fell

into a contented, deep sleep.

Epilogue

In the middle of the night, Serena stirred into

consciousness, awoken by an insistent prodding at her shoulder.

“But hang on! If we

can duplicate Alices by bringing them from another time or universe, why can’t

we do the same with presents? Then

there’d be enough to go around no matter how many of me there are!”

*Remember this is Serena we are talking about. Anything she finds ‘disturbing’ can safely be

assumed to be very, very bad indeed.

**But that of course is the secret of the Serena and Alice

tales. Each one, though it may include

graphic descriptions of the most stomach-turning torture, twisted and vicious

illustrations of the extremes of woman’s utter inhumanity to man culminating in

the agonies of multiple lonely meaningless deaths, is at its heart a love

story. A rom-com, if you like, but one

featuring charred flesh, splintered bones, gouged eyes, and the desperate echoing screams of the lover’s doomed victims.

Notting Hill, eat your heart out.

*** Another paradox, if you will, as there is obviously

no way that any male under Serena’s control would make it to a ripe old age

like that – unless being subjected to some very long-running torture (she is

proud of having used her time machine to set up a “slow drip” experiment in which a hot beaker of tar drips onto

awaiting male flesh no more often than once two or three years. It has been running for over thirty years already).

… oh and a little vignette of an extra tale, for those who have read down this far. Since we’re on the theme of parallel universes…

“I’m not sure, Mistress”, W said, nervously eyeing the futuristic headset. “I’ve tried a couple of VR things before and they’re just mainstream porn – pounding away at a gasping naked girl just isn’t my thing, you know?”

“Oh just relax, W” Mistress Valerie tutted. “Honestly, it’s bad enough you shrieking like a little girl every time I tap you with a paddle… just try this, OK? Even though you’ll feel everything, it can’t do you any real harm, you know that. And I promise it’ll be kinky enough – in fact, I guarantee it. You’ll see.”

So W lay back and let his Mistress fit the complicated apparatus over his head, then watched her attach the various tubes and cables to the control equipment. She pressed a few buttons and W flinched in fear as he felt the nanotubes snake into his flesh, to bury themselves deep inside his brain, but – coward though he was – he trusted his long-standing Mistress and had let her secure his wrists before she started. She patted his hand reassuringly.

“Now… you’ve got an exit, like a safeword. Your wrists are secured but if you get worried, you can just tap the index and middle finger of your right hand together three times and you’ll come straight back, OK? Now… are you ready?”

“Yes, Mistress. Erm… if I may, what’s the theme of the fantasy you’ve chosen for me?”

“But that’s the point, W. I don’t choose. It just looks inside your mind, finds a fantasy that you find exciting and makes it real for you. So it’s bound to be something you like, you see?”

“Oh, yes, I suppose so Mistress” W said, as the real world started to fade, to be replaced with the inputs from his new neural connections.

“Only…” he had a sudden thought. “Mistress, no! Wait! Please! Some of my fantasies are a bit – “

But it was too late. W found himself in a clinical white space, still apparently secured to a couch. He saw a young woman seated in front of him, blonde curls cascading around her perfect face, her big blue eyes staring right at him. She was the most beautiful girl W had ever seen. But something about her expression alarmed him.

Then he became aware of another woman standing by his side, dark-haired this time, wearing a lab coat. She seemed to be fixing something onto the fingers of his right hand, holding his index and middle fingers in a rigid V-shape, unable to move. W felt a stab of dread in his stomach.

“Hello ‘Servitor'”, smiled Serena, looking down at him. “We’ve both been so looking forward to meeting you, after all this time and all those things you wrote about us. Haven’t we, Alice?”